In the movie Kingsman: The Secret Service, the billionaire villain Valentine describes the relationship between humans and Mother Earth as that akin to the relationship between a virus and its host. The host develops antibodies to fight the virus. If the antibodies work, the virus is destroyed. Else, the virus takes over the host and destroys the host. But without the host, the virus also dies. Either way, the endgame is that the virus dies. Valentine’s view is that if humanity continued down the current path unchecked, eventually that would lead to the end of humanity itself. That fatalism has a lot of truth in it. Valentine’s strategy was to cull humanity. Of course, the hero stops him, and humanity is saved to live another day. This is the familiar storyline around numerous thrillers including Dan Brown’s Inferno.

Then there are the real-life billionaires like Elon Musk whose own solution to the problem is as simple as it is absurd. Their view is that since life on Earth is doomed anyway, why not spend billions to perfect the technology that allows us to relocate to Mars or to the Moon. Just leave Earth to those who can’t afford that one way ticket. This strategy, not far removed from science fiction, loses sight of the realities of how societies work and what makes us happy. Really, what is the objective? A wretched survival or a happy existence or non-existence? More likely, this is just extreme egg-headed capitalism at work!

This fatalism has many aspects to it. You have the debilitating possibilities of AI and biotechnology, the increasing potential for global pandemics, social unrest due to the rising wealth inequality, extreme geopolitics, rise of totalitarian regimes, and so on and so forth. But nothing threatens the world like Climate Change. All else is just a bunch of glitches in just one species’ existence. Climate change threatens the entire ecosystem, and we potentially take the Earth backwards by many millennia of evolution and development. If we can save the Earth, we save ourselves. If we only try to save ourselves, it’s the virus outcome… humanity will eventually go down along with Mother Earth.

Before the advent of modern religions and the insatiable desire of humans for power, prestige and wealth, most humans worshipped nature and maintained a healthy symbiotic relationship with it. We can’t recreate those days, but we can recreate that theme. We need to do that if we hope to make the World a Better Place for You, for Me, for our Children and for the beautiful Flora and Fauna on this Earth. Like David Attenborough said, “We need to learn to work with nature and not against it”.

Fortunately, we have the more sensible billionaires using the same billions, not to escape Earth, but to make Earth more liveable. People like Bill Gates realize they have no meaningful reason to accumulate their enormous wealth. A lot of their wealth is given away to charitable purposes or risked as investments into companies that are developing new technologies to Save the World for our Children.

Many years ago, diving in the calm turquoise waters of Maldives, I came across a large patch littered with bright white corals. It looked beautiful. But something was wrong. There wasn’t any fish or other marine life around. When I surfaced and asked, my dive master explained that these corals are dead. This was basically a graveyard of corals. They had bleached due to the warming waters. That was a shock to me. As years went by, news of coral bleaching became more and more common across the globe. Very few people understand how deeply this impacts human beings and the marine ecological balance. And even fewer understand how much the terrestrial ecosystems depend on the marine ecological balance. But that’s a topic for another day. Meanwhile, here’s some poop for thought.

These days, news of wildfires, floods, droughts, unseasonal snow and rainfall, extreme temperatures, etc is becoming more and more common. The Maldives dive woke me up to the climate change problem. But it still didn’t sink in fully. Over the last years, my commitment to climate change was limited to corporate mumbo jumbo and driving an EV car. But the more I listened to trusted podcasters and watched documentaries from trusted sources, the more I realized how serious the problem was. But the information was scattered and confusing. As usual, I needed notes to bring structure to my thought.

Recently I read the book, How to avoid a climate disaster, by Bill Gates. What I really liked about the book was his structured presentation of the problem, the facts, and potential solutions. I think Bill Gates probably suffered the same problem I did… a lot of scattered information. He wanted to make it easier for the rest of us stepping into this discovery. It’s a beginners guide and may not be for someone who is already deep into the subject, but for the rest of us, it is an excellent overview. However, while he has gone in depth on topics he is invested into, a lot of important topics don’t get coverage. Also, the book was published in 2021, the content is very USA centric, and the field is fast evolving. For my blog here, I have borrowed on his overall structure and also on a lot of the facts and content. So, wherever I refer to “The BG Book” I’m referencing this one. But I have also researched and included content from many of the missing topics, localized some content to the Indian context and added my own opinions.

This isn’t a typical blog. It is reasonably extensive literature research and is a long read. I’ve tried to cover the breadth of climate change topics starting with the problem statement, the broad solution, the obstacles and the solution toolkit. I’ve tried to keep the content on the solution toolkit only as deep as necessary to get a good feel for what could work and what may not. The intent has not been to get to very technical depth. Treat this blog as a comprehensive roadmap and quick reference guide, if you may. I hope to keep the content updated.

The Problem Statement

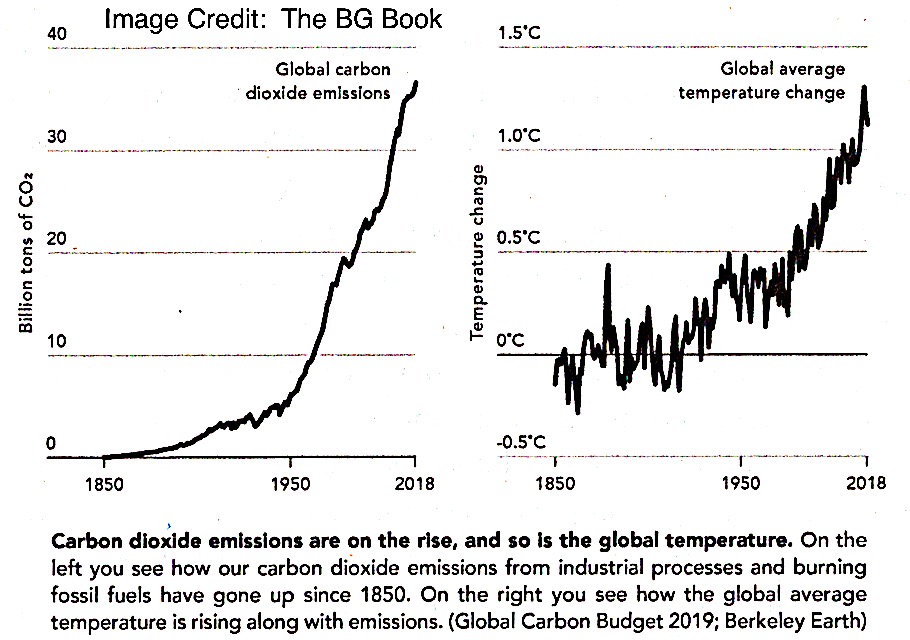

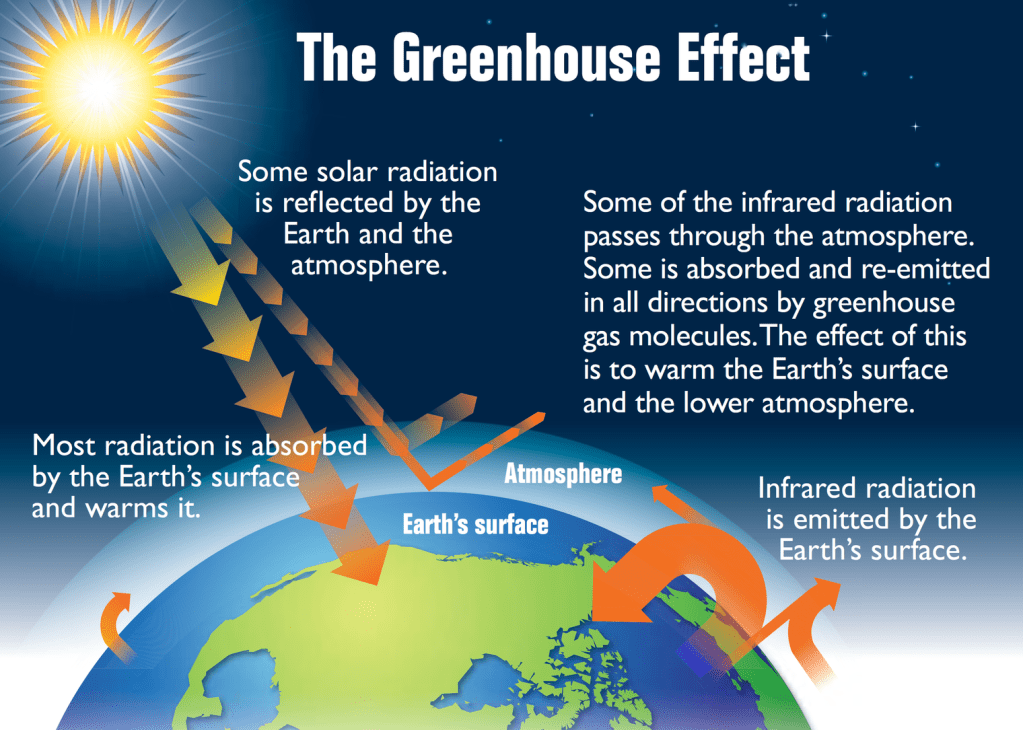

52 billion tons of greenhouse gases (GHG) See detailed endnote. That is the net amount added to the atmosphere every year. These gases stay in the atmosphere for a long long time. Something like 1/5th of the CO2 emitted today will still be in the atmosphere in 10,000 years. How’s that a problem? For millennia, Earth has radiated back to space all of the Sun’s energy that hits it, thereby maintaining a thermal equilibrium. But these greenhouse gases have changed that balance in the past century due to the Greenhouse Effect See detailed endnote. As their quantities accumulate in the Earth’s atmosphere, less heat gets radiated back and so the Earth is getting progressively warmer.

Interestingly, during the last ice age (about 10,000 years ago), when the Earth was largely unliveable, the average temperature was just 6°C lower than today. Right now, we have an average temperature increase of just over 1°C compared to pre-industrial times. In the Paris Agreement of 2015, it was agreed to limit greenhouse gas emissions to levels that would prevent global temperatures from increasing more than 2°C above the temperature benchmark set before the beginning of the Industrial Revolution.

2°C doesn’t sound like a lot, except when you compare this with the fact that a drop of 6°C takes us to the unliveable ice age, and the existing 1°C increase has already given us extreme weather events. The massive Australian, Canadian and US wildfires, massive snowstorms, powerful typhoons, unseasonal heat or cold waves, coral bleaching, severe droughts, severe glacial burst floods, and so on are all in the news, and can’t all be blamed on the LA mayor.

Of course, the existing 1°C increase is an average over seasons, and over the entire Earth. Individual seasons, individual locations and individual years are now seeing swings far beyond that, with cold waves during winters and hot waves in summers. Places that never saw snow now start to get snow, whereas skiing slopes are now investing in artificial snow making machines and the arctic is losing its ice cap. Islands and coastal regions are getting submerged due to rising sea levels.

Based on current models, if we don’t reduce emissions, we will probably have between 1.5°C to 3°C warming by mid-century and between 4°C and 8°C by end of the century. That’s devastating. Note that the difference between a 1.5°C and 2°C increase looks small mathematically. But the impact has been modelled to be 100% worse, and not 33% worse.

For the climate change sceptics, even if we assume that we can’t blame climate change for any particular event, it is clear that climate change has increased the odds of these incidents happening and that these incidents are getting more severe. Were the LA wildfires of Jan 2025 caused by the Mayor of LA or was it due to climate change? That’s not the question. Has the world seen more climate incidents this past one year? Of course, it has. Will there be more hot days in future? Will storms get more powerful? Will the artic ice cap melt completely? Will the Polar Bears go extinct? Yes, yes, yes, and yes.

In the detailed endnotes, you will see a brief compilation of the implications of climate change.

The Solution

The solution to prevent a climate disaster is to get the annual GHG additions to zero. This is simply referred to as “getting to net-zero” in climate change jargon. Note the operative term “additions”. It is not practical to get to absolute zero GHG emissions. Remember, even as we breathe, we are emitting CO2. At Net Zero, we balance all GHG emissions with the various carbon sinks, thereby stopping net GHG additions. The most easily recognized carbon sink is a forest, and if you read my previous link about whale poop, you will realize that phytoplankton in the ocean are the unspoken superheroes. Forests and phytoplankton absorb CO2, store the carbon within themselves, and release O2 as part of their photosynthesis process.

The Paris Agreement is an international treaty adopted in 2015 at the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21) in Paris where it has been agreed that countries will get to Net Zero within a timeframe that limits the average temperature increase to 2°C above pre-industrial levels, with efforts to keep it to 1.5°C. While the agreement itself hasn’t mentioned a timeline, many countries like the EU, UK, Japan and South Korea have set 2050 as their net-zero deadline, whereas China chose 2060 and India picked 2070.

As seen in the above graph, just reducing the GHG additions is not sufficient. It is absolutely essential to get to Net Zero. And because GHGs stay in the atmosphere for so long, the planet will stay warm for a long time after we get to Net Zero. If we need to go back to pre-industrial climate, we would in fact need to have net negative emissions. That is a noble cause, but currently not a practical ambition. Here is a breakdown of all human activities that produce GHG, broken in 5 major sectors. Getting to zero means zeroing out every one of these sectors.

| Category | Proportion | Absolute GHG emissions (billion Tons) |

| Industry (cement, steel, plastic, oil, gas) | 29% | 15.1 |

| Electrical Power Generation | 26% | 13.5 |

| Agriculture (plants, animals) | 22% | 11.5 |

| Transportation (cars, planes, trucks, ships) | 16% | 8.3 |

| HVAC (Heating, ventilation, cooling, refrigeration) | 7% | 3.6 |

| Total | 100% | 52.0 |

Getting to Net Zero emissions is hard, but not impossible. During the COVID-19 pandemic, when we had a massive reduction of economic activity, a massive reduction in commute and travel, and millions were put out of work, the net GHG emissions only reduced from 52 billion tons to 50 billion tons. This is proof that we cannot get to Net Zero simply by flying and driving less. Climate change Mitigation needs new breakthroughs in ways to produce electricity, grow food, produce goods, heat and cool buildings, and transport goods and people.

Considering that a certain amount of climate change is inevitable, we also need newer methods of Adaptation and Coping. Methods to be able to predict incidents and prepare safety measures, methods to improve crop yields with low water utilization, improvements in city planning, etc.

The Obstacles

Before we get into the solution landscape it helps to understand what’s holding us back. A big chunk of our GHG emissions come from fossil fuels. Unfortunately, fossil fuels have become so pervasive it is difficult to fathom any aspect of our lives without them. The plastic in our toothbrushes, the packaging of our grocery, the fuel running most vehicles, the electricity that we use… all are intrinsically linked to fossil fuels. The fossil fuel industry is not a villain, it was one of the great enablers of development. But now the time has come to make the switch. But that isn’t easy. The world’s energy industry is worth roughly $5 trillion a year (about 6% of the global GDP) and is the basis for the modern economy.

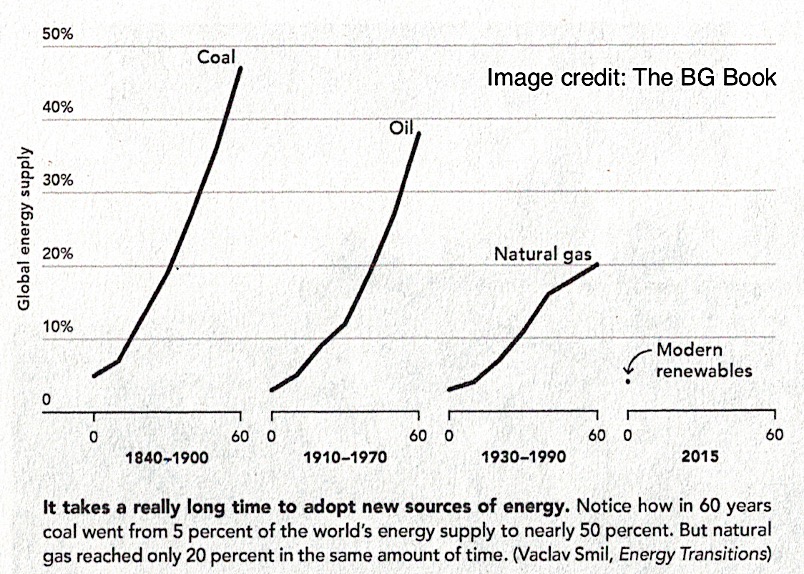

You can’t just upgrade from Version Fossil Fuel to Version Green, like you could with software. Energy transition is a gradual process, it takes time. Even coal took 60 years to go from contributing 5% of the world’s energy to nearly 50%. Oil took 50 years to go from 5% to about 40%. And in the past, we moved from one source to another because the new one was cheaper and more powerful. Unlike what we may feel, fossil fuels are actually quite cheap. Even in India, it costs just double that of a bottle of premium mineral water. In many countries, it is cheaper than a soft drink.

The inertia of transitioning such a large industry also comes from the size of capital invested. It is one thing to upgrade a $1,000 computer once is 3~5 years. But a $1 billion investment in a coal power plant is there to stay a long long time… 30 years or more, and there are many of these commissioned not too long ago.

Then there is the need for infrastructure development, especially in the poorer countries. That needs a lot of steel and cement, again big emitters of GHG. As standards of living go up, the demand for housing, electricity, cars, etc goes up, again ending up with higher emissions. It would be immoral and impractical to try to stop populations that are lower down the economic ladder from climbing up.

Government policy and regulations are another aspect that needs major upgrades to change the status quo. Laws relating to pollution or efficiency do not explicitly consider climate change related emissions. For example, industry is subject to pollution control laws and have continuous emission monitoring systems, but these aren’t accounting for CO2 emissions, just the traditional pollutants. Vehicle efficiency and pollution control standards do not put limits on CO2 emissions.

Last, but not the least, is the lack of climate consensus. There are a small and vocal, but powerful group of people, with strong social media influence, who are not persuaded by the science. For them, accepting the climate change reality would mean a dent to their profits. They are akin to the tobacco industry, that even in the 1950s advocated smoking for better health and created a strong disinformation campaign to support their claim… they even got doctors to vouch for smoking. Then there are those who accept climate change to be a problem, but believe we are already doing enough to mitigate it… planting a tree here or there, setting up some solar generation, making a small shift toward EVs. The reality is far from this. As we saw earlier, something as dramatic as the COVID-19 slowdown only dropped 4% of the net emissions. Big steps are needed. The last of the consensus problems is to get global cooperation on this topic in a notoriously divided and right-wing world.

The reason some people believe we are already doing enough is because a lot of numbers are thrown around the climate change topic and some of it sounds fantastic. To make sense of what they mean, we need to be able to gauge it on a relative scale. For example, if an industry reduces its carbon footprint by 17 million tons per year, that sounds like a lot and exciting. But that is just 0.03% of our 52 billion tons of GHG. So, any such figure needs a comparison with a meaningful baseline and a timeline. To help gauge the quantum of all these numbers, refer the detailed endnotes for some baseline figures.

The Solution Toolkit

Now that we understand that the solution to the climate change crisis is to get to net zero emissions, I’ll try and cover all the major solutions currently on the landscape. Some of these are established and some are in early stages. We will mostly cover technology solutions. But above all, like any change management process, technology is only an enabler. There are cultural and behavioural changes needed. That would involve policy changes, education and awareness, consensus building, and today’s mantra – deal making. For now, my major source has been The BG Book, and I know that there are major trends that have missed mention in the book. Some of these I have added on my own, and I hope to continue doing that. Major missing topics included that of carbon trading and green hydrogen.

A recurrent theme will be that of a Green Premium for each solution. That’s also described in the detailed endnotes. Put simply, it is the relative price of adopting that green solution. For example, jet fuel retails for $2.22 per gallon in the US, whereas advanced zero emission biofuels are available at $5.35. So, the Green Premium in this case is $3.13 i.e. a 140% premium.

Another recurrent theme is that every solution has its share of challenges, either technical or commercial or environmental or social. Recent failures of Northvolt (a battery manufacturer) or Nikola (a hydrogen truck manufacturer) don’t mean those technologies are failures. My best guess is that these companies were poorly managed. The Chinese have proven that battery technology is commercially viable. I strongly believe hydrogen-based fuel cell technology will also be commercially viable eventually. My point is that proponents of one solution will declare doom of other solutions at the slightest hint of difficulties. But we don’t have the luxury of picking and choosing. We need to support all these solutions so they can continue to be developed and perfected.

Let’s now delve into the fun stuff.

Carbon Capture (CCS and CCUS)

I start with these tools of last resort in the solution toolkit. If nothing else works, this may be the only way to cut our CO2 additions. CCS stands for Carbon Capture and Storage. CCUS stands for Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage. CCS and CCUS are spoken of in a similar vein but have fundamental differences. With CCS, CO2 is captured from a source of emission, transported to a storage location and buried deep underground. The storage could be in saline aquifers (ref. Sleipner gas field) or into basaltic rock in geothermally active regions like Iceland where they mineralize as calcium carbonates (ref. Carbfix). With CCUS, the CO2 is utilized by pumping it into depleted oil and gas fields, thereby pushing out more oil and gas and extending the life of the field. This is called EOR (Enhanced Oil Recovery).

A study by IEEFA of 13 flagship CCS projects concluded that failed/underperforming projects considerably outnumbered successful experiences by a factor of 10 to 3. Also, 73% of the projects are CCUS for EOR and the green credentials of EOR are controversial. The objection is “Successful CCUS exceptions mainly existed in the natural gas processing sector serving the fossil fuel industry, leading to further emissions”. I don’t fully understand that topic yet. If CO2 is used to extract fossil fuels, but that CO2 remains stored underground, I think I’d be OK with that for now. Fossil fuels are not going away anytime soon, and their extraction method is immaterial. But if the pumped CO2 is dissolved in the extracted fuel only to be released later as combustion CO2, this is a farce. I need to figure this out.

CCS is also quite expensive and would only get economically viable when governments start to set extremely steep penalties for GHG emissions. Today, the cost of sequestering a ton of CO2 using CCS is about $200. As a thought experiment, if we consider CCS as the only solution in our toolkit, removal of the 52 billion tons of GHG would cost about $10.4 trillion viz. 10% of the world GDP. If that cost eventually comes down to $100 per ton, this is still a massive amount of money at $5.2 trillion viz. more than the GDP of Germany, currently the 3rd ranked country by GDP in the World.

Clearly, the technology is far from ready for global deployment. In any case, this is an extremely inefficient method for solving the world’s GHG problem. Apart from the cost, it is also unclear if we could store hundreds of billions of tons of CO2 safely. Geologists realize that injecting CO2 is more complex than extracting hydrocarbons. There are concerns about pressure limits, reservoir integrity, fluid migration and geochemical reactions. Problems at the two CCS “success stories” is a case in point. The IPCC’s Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage Special Report stated: “CO2 storage is not necessarily permanent. Physical leakage from storage reservoirs is possible via (1) gradual and long-term release or (2) sudden release of CO2 caused by disruption of the reservoir”. What if the CO2 ends up escaping somewhere else or causes some other unintended consequences. I honestly believe that humans are quite shortsighted about the long-term impacts of playing with nature. And who’s responsible for the long-term monitoring and maintenance of these underground storage sites? The CCS company would pack shop and leave after their assigned contractual period after benefitting from all the subsidies, grants and tax credits for capturing carbon. But after that period, does the liability again fall back on the taxpayer? CCS/CCUS should not be an excuse to greenwash and encourage the establishment of new fossil-based fleets in different industries. If gas operators commit to installing CCS only to gain license to operate a new gas extraction, but as history has proven, fail to deliver on those CCS obligations, is there a suitable penalty that compensates the climate change impact? The high profile Gorgon CCS is a case in point on this topic. Overall, this solution gives me little comfort. It is just kicking the ball down the road, and not focusing on fixing the errors in our ways.

On the other hand, there are two aspects that work in favour of CCS and CCUS. First, it can work as a mitigation measure for any sector. At the end of the day, this may be the only option for some hard to abate sectors like cement, at least in the short term till greener options are innovated. Second, it is backed by the big guns – the fossil fuel industry. These days, where deal-making is the in thing, if we can hold them accountable to performance of these plants and to their long-term maintenance, they have the deep pockets needed to make this work. If we look at the bright side, getting 3 out of 13 projects working is not bad for a proof of concept and there are lessons to be learnt in those 3, as well as in the failed 10.

Refer the detailed endnotes for some further commentary on this subject.

Green Hydrogen

Use of Hydrogen (H2) holds promise across almost all 5 sectors and is considered a cornerstone of achieving net zero emissions. Various countries have bet on its potential and it’s not uncommon to hear talk of building a “Hydrogen economy”. The sheer breadth of applications where hydrogen could be applied means that these bets are reasonably diversified and something significant should come out of it. Before we delve deeper, an understanding of the colour attribute of Hydrogen is important.

What’s with all these colours? Isn’t Hydrogen colourless?

Yes, Hydrogen is colourless. But the attributes Grey, Blue and Green are used to refer to how it is produced and are indicative of the extent of GHG emissions involved in their production process.

Grey hydrogen is produced by the steam methane reforming (SMR) process where natural gas reacts with water at high temperatures to produce CO2 and H2. The CO2 is released to the atmosphere. The hydrogen thus produced is called grey because of the extensive CO2 emissions as part of the chemical process and the use of fossil fuels to heat the SMR reactor to maintain its working temperature at 800~900°C. There are even worse colours – black and brown – which use a similar chemical process but use black (bituminous) or brown (lignite) coal instead of natural gas. Their GHG impacts are even worse than that of grey hydrogen.

Blue hydrogen is produced with the same process as grey, but the CO2 is purportedly captured and stored by CCS. Blue hydrogen is therefore claimed to be carbon neutral. But that couldn’t be more wrong. Recent research from Cornell and Stanford Universities found that: “Considering both the uncaptured CO2 and the large emissions of unburned, so-called ‘fugitive’ methane emissions inherent in using natural gas, the carbon footprint to create blue hydrogen is more than 20% greater than burning either natural gas or coal directly for heat, or about 60% greater than using diesel oil for heat”. Researchers at the Australian National University said: “We find that emissions from gas or coal-based hydrogen production systems could be substantial even with CCS, and the cost of CCS is higher than often assumed”. We’ve also spoken about the challenges with CCS, and while CCS may be a fallback for hard to abate industries, the hydrogen industry is not hard to abate. CCS/CCUS should not be an excuse to greenwash and encourage the establishment of new fossil-based fleets in different industries. So, let’s not be fooled. Blue hydrogen is not “clean” hydrogen! In any case, green hydrogen is expected to be cheaper than blue hydrogen by 2030, and so these projects are destined to become white elephants.

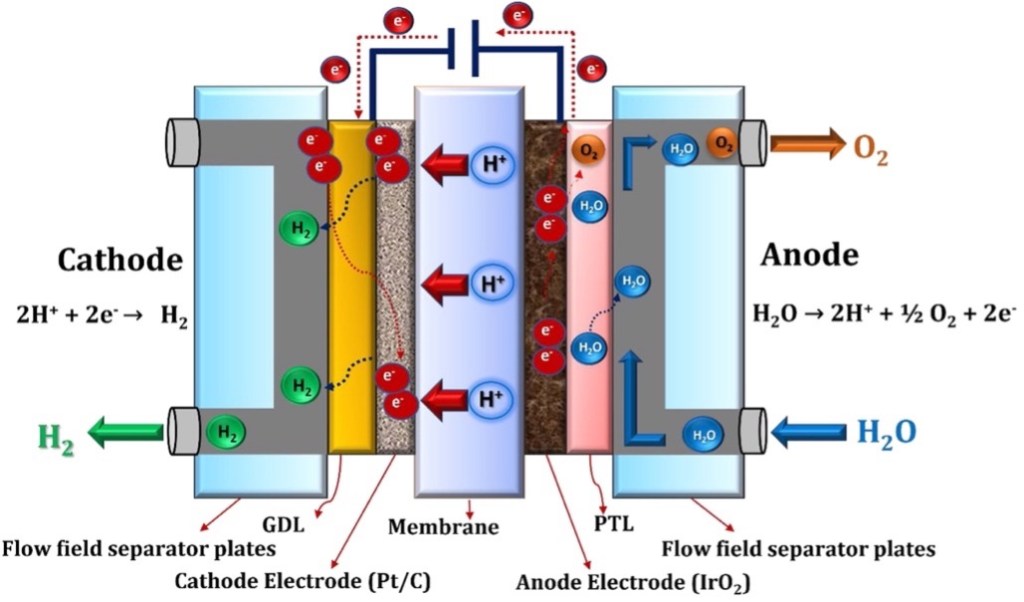

That brings us to the hero of the story: Green Hydrogen. This is produced using the electrolysis process. The process is simple, in principle, and has been available for centuries. Electricity is passed through water (H2O) in an electrolyser to break it into hydrogen (H2) and oxygen (O2). The prerequisite for this H2 to be called Green is that the electricity is sourced from renewable sources. Here’s some detailed content on the technology. So, what’s needed to produce green hydrogen is just a lot of water and a lot of green electricity.

Applications of Green Hydrogen

The excitement with Green H2 is in its potential in decarbonising a lot of sectors. In later sections on Industry, you will see that Green H2 is key to decarbonise steel production. There is potential also in the cement industry to use it as a fuel. Black, brown and grey hydrogen have been industrially produced for long for synthesis of ammonia, fertilizers, ethanol, methanol, and other chemicals. Switching these chemical applications to green hydrogen will help decarbonize these industries too. In the Transportation sector, you will find Green H2 holding promise for decarbonising trucks, trains and ships, and questionably, airplanes. It is also possible to produce synthetic fuels by combining H2 with atmospheric CO2, thereby creating a zero-carbon hydrocarbon fuel. In the Electrical Power Generation sector, it can help as an energy storage solution to tackle the intermittency problem. It can also be blended with natural gas, to reduce its CO2 footprint, when used for power generation in existing infrastructure, and for heating and cooking in residential and commercial sectors.

Underlying most of these applications is the fact that when H2 is used, it typically combines with O2 to form water vapour. So, you have the safest possible byproduct, making it such a darling of the net-zero strategy.

Fuel Cells that generate electricity is another technology that finds use across many of the above applications. A fuel cell is the exact reverse process of the electrolysis process used to produce H2. In reverse electrolysis, H2 reacts with O2 in atmospheric air to produce electricity and water. A catalyst at the anode separates hydrogen into positively charged H2 ions and electrons. The O2 is ionized and migrates across the electrolyte to the anodic compartment, where it combines with H2. A single fuel cell produces 0.6~0.8V under load. To obtain higher voltages, several cells are connected in series.

Challenges with Green Hydrogen

Clearly, Green H2 seems too good to be true. Surely, there must be a catch. Absolutely. This technology still has many wrinkles to iron out.

H2 is extremely energy dense by weight. But since it is a very light gas, its volumetric energy density is very low. Below is a comparison to petrol. What this means is that if H2 were to be used as a fuel in a car, you would need high pressure tanks that are 5~10 times the size of the existing fuel tank to be able to deliver similar driving distances. There isn’t going to be much boot space, is there?

| Fuel | Gravimetric Energy Density (MJ/kg) | Volumetric Energy Density (MJ/L) |

| Hydrogen | ~120–142 MJ/kg | ~8.5 MJ/L (at 700 bar, compressed gas) ~2.7 MJ/L (at 250 bar, compressed gas) ~0.0108 MJ/L (uncompressed gas) |

| Petrol | ~46.4 MJ/kg | ~34.2 MJ/L |

The need for high pressure storage of H2 leads to many further difficulties. H2 molecules are really small. This means that it can seep (permeate) through metals the same way that we lose air through the rubber in our vehicle tires. So, there’s always a gradual loss over time. This also causes the metal to become brittle and weaken over time, causing storage tanks and pipelines to leak or rupture. Compressing H2 to such high pressures involves a lot of energy use – up to 10~15% of the energy content of the H2 – thereby reducing the overall efficacy of this solution. Being extremely energy dense, H2 is highly inflammable, and comes with fire and explosion risks. Leakages are also not easy to detect. Existing fuel transport and storage infrastructure like pipelines, tanks, transport trucks, transport ships, etc cannot be repurposed for H2, and would need complete redevelopment.

According to this Bloomberg NEF report, the cost of green H2 is a whopping $4.5~$12/KG, depending on where it is produced. Grey H2, on the other hand, costs $0.98~2.93/KG, whereas blue H2 is $1.8~$4.7/KG. But electrolyser costs are also falling fast. It is expected that green H2 cost would hit $2/KG by 2030 and $1/KG by 2050. In India, Petrol is about $1/KG today. But we have to remember that H2 delivers almost 3 times more energy per KG and hence, can afford to be 3 times more expensive than petrol. That makes H2 already not that much more expensive than petrol, with a promise of getting significantly cheaper.

The list of challenges is large, but not insurmountable. There’s a lot of research ongoing to mitigate these challenges. For example, new materials are being developed to allow for solid-state storage where H2 binds chemically to these materials, allowing for safer and more compact storage. However, keeping an honest view on these challenges helps to be able to channel development effort and investments into areas that seem most practical.

Having covered the sector agnostic solutions, CCS and Green Hydrogen, we now look at each of the 5 major sectors that contribute to GHG emissions and look at the solution toolkit applicable to each of them.

Sector 1: Electrical Power Generation

While electricity is only 26% of the overall GHG problem, the reason it rightfully gets a lot of attention is because it constitutes more than 26% of the solution. Electricity is the key to reducing the emissions from other categories like industry, transportation and HVAC, where fossil fuel based thermal processes can be changed over to electricity powered processes.

Today, fossil fuels contribute about 2/3rd of the total electricity generation. That’s because they are cheap, they can be built close to the user of power, the technology is established, and the fuels are cheap and easily available. Most countries take various steps to keep fossil fuels cheap. International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that government subsidies for consumption of fossil fuels amounted to $400 billion in 2018 globally.

The BG book estimates the green premium for electricity in the US at 1.3 to 1.7 cents per KWh, that’s roughly a 15% premium over the retail rates today. In Europe, it is estimated at about 20%. In absolute terms, this may not be a very steep hike in one’s electricity bill… approx. $18 a month for the average US home. But this green premium is going to be different for different countries depending on the availability of renewable energy sources like hydropower, strong winds, year-round solar power, etc. In poor countries, in the absence of that or where the green premium is not affordable, the trend continues to be to build coal-based power plants. As of mid-2019, about 236GW of coal plants were still being built around the world. As I write this blog <Feb 2025>, India had over 80GW under various stages of implementation and planning.

The intermittency challenge

The main reason green premiums are high with electricity is the problem of intermittency. A solar panel will generate power only when the sun is shining on it, wind power will only flow when the wind blows, and hydropower needs flowing rivers. This intermittency could be a daily cycle, like with Solar. It can also be seasonal (summer, winter, monsoons) with solar, wind and water flow intensities varying with the season.

Complex problems are likely when the dependency is heavily on intermittent renewable sources. Take the example of Germany who invested heavily in solar capacity. To handle the intermittency, they installed more capacity than their total demand so that during the leaner period, they could still draw enough power. In June 2018, Germany produced 10 times more solar power than in December 2018. They had to send the excess power to Poland and Czech Republic, causing unpredictable swings in the cost of electricity and potentially destabilizing the grid.

I also remember the time I was in Switzerland during the solar eclipse of 2015. This was a massive pressure test of the grid’s resilience. During a solar eclipse, there’s obviously a sudden drop is solar energy for a few minutes and then it is back on in its full glory. But industries and offices and homes go on as usual, and so the power demand doesn’t change while we have this supply glitch. In the absence of batteries, fossil fuel-based power plants need to quickly ramp up their power generation in those few minutes and ramp down just as quickly. This is not an easy task since they have their inherent inertia. If not planned and executed right, the grid was certain to collapse and send most of Europe into a blackout. Fortunately, the planners did a good job, and the entire incident went off without a glitch. This was easy since this was a foreseen event, and the planning and coordination could be done weeks in advance. Unforeseen events or poor planning could lead to unfortunate outcomes.

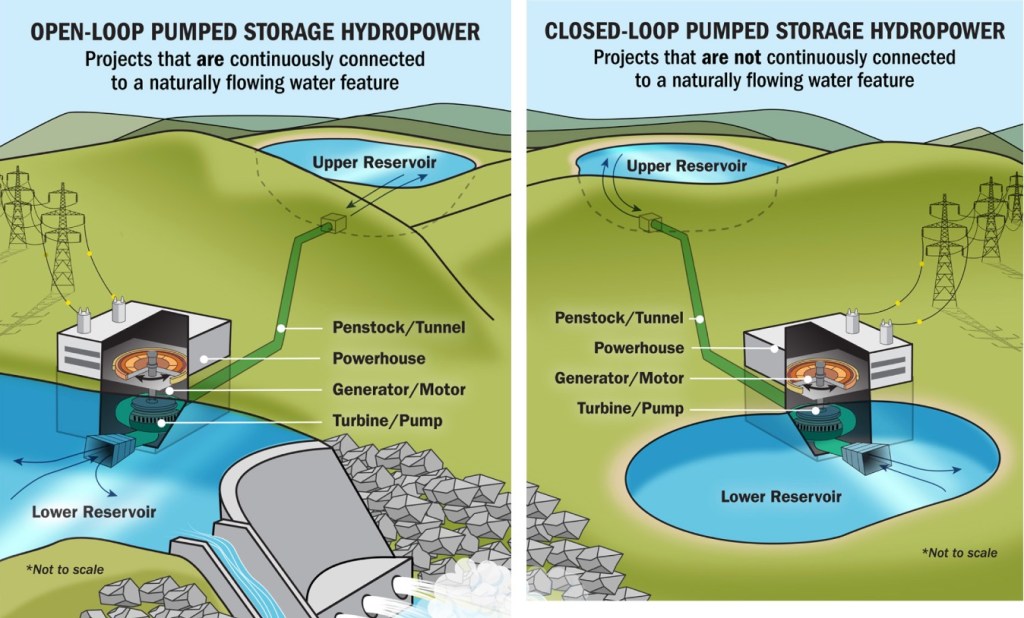

The intermittency can be handled by storing excess power in storage devices. The two most commonly considered solutions are BESS (Battery Energy Storage Systems) and PSP (Pumped Storage Projects). Using batteries for energy storage is relatively easy to understand. When the renewable source is producing excess energy, that energy is used to charge massive battery banks. When the energy intensity drops, these batteries take over and deliver the required energy. Pumped Hydro storage or PSP is another option. Think of this as a dam, but instead of a downstream river, you have a downstream reservoir, apart from the upstream reservoir. Excess energy in the grid is used to pump up water from the lower reservoir to the higher reservoir. When the grid demands power, the water flow is reversed, and this system now operates like a hydroelectric power station.

Honestly, I’m no fan of BESS. They have a shorter life span (10 years compared to 40 years for PSP) and have their own carbon and ecological footprint during their manufacture and end-of-life. The global critical mineral shortage is also exacerbated by this demand for batteries. Their use case may be more in terms of handling rapid short-term fluctuations since the PSP solution cannot swing up and down too dynamically. However, battery technology is fast evolving, and their costs are coming down continuously. So, this remains a major option for grid scale storage.

Recently <Feb 2025>, the Indian Ministry of Power has issued an advisory mandating a minimum of 2-hour co-located energy storage systems (ESS) for new solar projects, equivalent to 10% of the installed capacity to enhance grid stability. Currently, India’s total ESS capacity is 4.86 GW (4.75 GW from PSP and 0.11 GW from BESS). According to the National Electricity Plan, India will require 73.93 GW/411.4 GWh of ESS by 2031-32 to integrate 364 GW of solar and 121 GW of wind capacity. This includes 26.69 GW/175.18 GWh from PSP and 47.24 GW/236.22 GWh from BESS.

Other storage solutions being experimented on include thermal storage and hydrogen storage. With thermal storage, excess energy is used to heat salt into a molten state. This molten salt is then used to run a steam turbine when power is demanded. These can be retrofitted into decommissioned fossil fuel plants. One could also use the excess power to produce and store green hydrogen. When power is demanded, that can be converted back to electricity using fuel cells.

Fortunately, peak power demand happens during the day when all industries and offices are operational. So, it is also possible to model the energy demands of the grid and use renewables to deliver during the peak demand periods. That can take off the need for some of the fossil fuel capacity that is set up to cater to the peak demands.

Extending this approach is the concept of load shifting or demand shifting. This involves smartly managing power demand to smoothen out the peaks and troughs. At home, this could mean that when the car is charging, the water heaters stop working, or that the car charging starts up when other loads are low. With industrial processes, it may be possible to run some of the energy-intensive processes like water treatment or hydrogen production when electricity is in excess. This kind of balancing can be scaled up to a larger demand base to reduce the need to install capacity just to meet the peaks.

This would work best when incentivized with dynamic electricity pricing. If electricity prices vary depending on demand and supply i.e. price goes up when demand is high and goes down when supply is high, and that information is dynamically available to consumers, the smart consumer would program their power utilization to maximize the lowest price, thereby shifting their power demand from the peak demand period to the peak supply period.

Another important possibility is the interconnection of grids. Theoretically if all the grids of all countries are connected to each other, you could balance out the peaks and troughs across the grid to an extent that you probably don’t need much storage capacity. When it’s day in one part of the world, it is night elsewhere. When its summer is South Africa, its winter in Europe. While a globally interconnected grid may be a bit of a utopian dream in a divided world, it is practical to set up such interconnections on a regional basis. In the case of large countries, the low hanging fruit is to just interconnect the national grid.

I was surprised to learn that the grid in an advanced country like the USA is heavily splintered regionally, like their politics, and doesn’t allow the country to leverage the geographic diversity of energy intensities. If they did, it would allow every state to meet the emission-reductions goals with 30% fewer renewables than they would need otherwise. I believe countries like China and India are better off on this front. Here’s an excellent YouTube video on this topic from the channel Just Have a Think by Dave Borlace, a channel I trust 100% on Climate Change topics.

Hydroelectric Power Generation

Hydroelectricity i.e. dams, has been around for long and is an excellent source of green electricity. They also help regulate water flow for downstream riparian villages for flood control and irrigation. But they come with their share of problems. Behind the dam is a massive reservoir. To construct the dam, you need to displace local communities and wildlife to set up that reservoir. You also disrupt the lifecycle of aquatic creatures as has been seen with salmon. Salmon DNA is encoded with instructions to swim upriver to their birthplace to spawn. The obstruction by a dam leads to major decline in their populations. Dam construction can also be a major engineering challenge, and if not assessed and done right, can lead to seismic instabilities. And if the construction site has a lot of embedded methane, the release of this methane during construction can easily offset all the green benefits of the hydropower. And like most renewable energy sources, seasonal intermittency is a problem with hydropower too since you need flowing rivers to run a dam.

All said and done, this is still an attractive solution provided the environmental assessments are carried out diligently. Lots of dams are currently under construction including a dam on the river Nile by Ethiopia (opposed by Egypt) and a dam on the river Brahmaputra by China (opposed by India). And therein lies the other problem with dams. Downstream riparian states normally lose out in the equation, and finding a consensus there can be difficult. In India, about 14GW of hydel projects are currently under construction and another 24GW is under planning <Feb 2025>.

Meanwhile, dams are also being removed at a rapid rate across the globe either because they have become old and unsafe, or because their original purpose related to irrigation is no longer relevant. And in some cases, this was done just to regain lost aquatic ecosystems and support ethnic communities, thank you.

Solar Power Generation

Today, solar power generation doesn’t need much introduction. If we don’t already have a solar panel installed in our house, we most certainly have seen it on the rooftops of some of our neighbours. As a power source for home, we would normally couple this with the main grid supply so that when the solar generation tapers off, we can tap power off the grid. Most of these domestic systems are in the range of 3 to 5KW capacity. If the intent is to be completely off the main grid supply, for example in remote locations, it is possible to buffer the system with batteries so that the batteries charge using the excess power during the day and provide power at night.

Solar power stations need to be at a different scale altogether to be able to make a dent on the grid power requirement. The largest solar power plant in the world happens to be in India. This is the Bhadla Solar Park, located in the Thar Desert of Rajasthan, with an installed capacity of 2.2GW, and covering an area of 56 Sq. KM (14,000 acres). The location gives the advantage of easy land acquisition and high solar irradiance but brings with it the problem of sandstorms dirtying the face of the solar panels. The face of solar panels (even those that aren’t in deserts) need to be kept clean to maintain efficiency, and this chore is best relegated to automated robotic wipers in these large installations.

The price of solar panels had been a hurdle in the past. Fortunately, the mass manufacture in China has helped bring prices down. Solar cells got almost 10 times cheaper between 2010 and 2020. The biggest challenges today with solar power generation is the intermittency problem mentioned before and the footprint. Compared to a fossil fuel power plant, a solar plant would require about 100 times the land to deliver an equivalent power capacity. That explains why they tend to be in remote locations which brings the added challenge and cost of transmitting this power over long distances to get to the power consumers.

A continuing area of innovation is relating to efficiency. Today, the best solar panels only convert about 25% of the received solar energy into electricity. The theoretical limit is considered to be 33%. Newer materials like Perovskite are being developed that would allow higher efficiencies, and thereby less footprint and hopefully even lower prices.

Wind Power Generation

Wind had been another source of power since medieval times. The design has obviously changed significantly since then. Today’s windmills (or more accurately, wind turbines), are tall, elegant structures arranged in wind farms, towering at a height of about 100m, with blade diameters of about 100m. Each turbine can generate up to about 3MW power. One of the largest onshore wind farms is the Mojave Wind Farm in California that is rated at 1.6GW capacity, consists of 600 turbines and covers an area of 130 Sq.KM.

Wind farms are great as renewable sources. They also suffer the same problem as solar relating to intermittency, footprint and the need for long transmission distances. The other downside is the potential impact on birds that could get killed by the blades of the many turbines when flying through a wind farm. I’ve seen mixed opinions on this topic and am not yet able to take a balanced view.

Wind farms are also located offshore to take advantage of sea winds which are inherently less intermittent. This also reduces the complexity of land acquisition and can be relatively close to large coastal cities, thereby reducing the transmission requirements. Today it is still a small fraction of the world’s power generation but is expected to go up significantly.

Nuclear Power Generation (Fission based)

Nuclear power is the only carbon-free energy source that can reliably deliver power day and night, through every season, almost anywhere on earth, that has been proven to work on a large scale. It is also the most efficient in terms of land utilization and construction material utilization.

However, high-profile accidents like the Three Mile Island in US, Chernobyl in Ukraine, and Fukushima in Japan put a spotlight on the risks of a nuclear power plant. No one, including me, wants a nuclear power plant in their vicinity. They are also quite expensive to build. Geopolitics also comes in the way of technology transfer and fuel procurement due to the possibility of the fuel, Uranium, being weaponized. Disposal of nuclear waste is also a major issue. Somehow, the combination of all these factors has led to near paralysis in development of nuclear power technology and proliferation of this energy source. In reality, nuclear power has killed far fewer people than road accidents or flight accidents or for that matter, even fossil fuel power plants. So instead of stopping development, this is now a great time to accelerate development in this field and find solutions.

Disposal of nuclear waste is clearly a big challenge and cannot be downplayed. Nuclear power plant safety is probably more easily sorted. Radioactive materials stay dangerous for thousands to millions of years. No human-made structure has or will last that long. For short term, spent fuel rods are stored in cooling pools or dry casks at reactor sites. Long term storage would be in deep geological repositories. However, building these is expensive, complex, and often delayed due to political or public opposition. Sending it out into space, destined for the Sun, could be an option, considering the advances in commercialization of space exploration. But it has its own set of challenges in terms of costs, risks and complexity of the mission. This seems to be a worthwhile application for Elon Musk’s SpaceX to crack.

From an India perspective, it has been heartening to see that the government has also recognized the potential of nuclear power. The current target <Feb 2025> is to ramp up to 100GW of nuclear capacity from the current 8GW by 2047. Participation by private players has been opened up, and legal issues related to liability that previously prevented technology suppliers from participating, are being sorted. What I also liked about the announcement was an allocation of more than INR 20,000 Crore ($2 billion) for R&D into Small Modular Reactors (SMRs). SMRs, as their name suggest are modular, making it easier to prefabricate in factories and assemble at site, and are smaller at 300MW, about 1/3rd the size of traditional reactors. It is heartening to see India taking the initiative to co-develop this technology. This is not just an opportunity to decarbonize India’s power generation but is also an opportunity to be a supplier of low-cost nuclear power plants to other countries. The success of our space research program shows that the will and the talent exist. But the inability to handle city waste brings the question of how capable we are of nuclear waste disposal. These are problems to be solved, and I am sure an area as sensitive as nuclear will get due attention.

Nuclear Fusion based Power Generation

This is recreating the Sun on Earth. Instead of releasing energy by splitting atoms (nuclear fission), nuclear fusion attempts to fuse atoms and release energy. This is in early experimental phases and is far from commercialization. The joke seems to be: “Fusion is 40 years away, and it always will be”. I won’t be delving deeper into this in this blog.

Geothermal Power Generation

This is another niche renewable energy source using the heat in the earth’s core. Water is pumped deep (4~5KM) into the earth’s crust where it superheats. This heated water is collected back up to the surface and used to run turbines and generate electricity. Currently, there is only about 15GW of geothermal power generation in the world. Not a topic I’ve studied in depth. I’ve seen documentaries of geothermal power generation in Iceland, and it looked exiting. But like with CCS, I can’t help but worry about playing God with Earth’s crust.

Biomass Fired Power Generation

This is a controversial topic. Biomass includes stuff like wood chips, rice husk and other agricultural waste. These can substitute fossil fuels in conventional power plants with some modifications. Burning biomass is considered to be carbon neutral because that product (for example, wood chips from a tree) absorbed a certain amount of CO2 from the atmosphere during its life and that same CO2 is now released back into the atmosphere during combustion. So, it should be a net zero. This logic makes sense if these chips are sourced sustainably, for example waste from agriculture, and the net CO2 absorbing capability of our flora does not drop. But when woods are cut down to make woodchips to feed these power plants, the logic fails completely. Trees take decades to grow, whereas their combustion happens in a jiffy. There is clear evidence that the shift to biomass has led to deforestation to feed these power plants. This then is a classic example of “greenwashing”.

Reduced Power Consumption

It is inevitable that the demand for electricity will rapidly rise in the future as poorer countries develop and their consumption increases, as non-electric carbon emitting processes are converted to green electric processes, and as the newest electricity guzzler on the block, data centres, ramp up capacity. But on the other hand, it is also possible that we reduce electricity consumption. It is said that the cleanest energy produced in the energy that was never used.

Motors in industrial processes are one of the biggest consumers of electricity and just swapping all of them to high efficiency variants will not only help reduce consumption but will also pay back for itself in no time. The same goes for any consumer of electricity like refrigerators, lights, fans, air conditioning, etc. The initial cost of buying a high efficiency variant may be a bit daunting, but it will invariably pay back in time with a lower electricity bill, and by the way, you helped reduce some carbon emissions, thank you.

Sector 2: Industry

We now move on from the Electrical Power Generation sector to the Industrial sector. At a 29% share (15 billion tons), industrial processes are the biggest emitters of GHGs. Steel and Cement are literally the bedrocks of infrastructure development but are also big CO2 emitters. The world produces about 4 billion tons of cement annually. The largest producers are China and India, with 50% and 10% share respectively. World steel production is approx. 2 billion tons annually, again with China and India leading the race with approx. 50% and 8% share respectively. For each ton of cement produced, 1 ton of CO2 is emitted and for each ton of steel produced, about 1.8 tons of CO2 is emitted. Clearly these two sectors account for more than 50% of the industrial emissions, and they are set to grow considerably over the next decades. Manufacture and production of fertilizer, paper, aluminium, glass, plastics, oil & gas, etc add up the rest of the industrial CO2 emissions.

Unfortunately, the BG book does a disservice to industry. Bill Gates concludes that “short of simply shutting down these parts of the manufacturing sector, we can do nothing today to avoid these emissions”. In reality, these industries have been conscious of their impact and a lot of work has been going into decarbonizing efforts, some of which I’ll cover. The BG book focuses on CCS as the solution for industry and calculates the related green premium as follows.

| Material | Average price per ton | CO2 emitted per ton | New price with CCS | Green Premium |

| Ethylene (plastics) | $1,000 | 1.3 Ton | $1,087 – $1,155 | 9 ~ 15% |

| Steel | $750 | 1.8 Ton | $871 – $964 | 16~29% |

| Cement | $125 | 1 Ton | $219 – $300 | 75~140% |

Competition in these commodities is fierce and so, even a small premium can make or break a manufacturer. But if government policy phases in an equivalent penalty over time for the dirty product, that would be an incentive for manufacturers to go green. As can be seen, even with CCS, the premium is not extreme for plastics and steel, and may not be a major inflationary trigger. I am not advising to nudge these industries towards CCS with the green penalties, but to use the CCS based green premium as a judge for a reasonable level of penalty applicable to an industry.

Cement Production

Cement is considered the hardest industry to abate. The first problem is that concrete is the second most consumed commodity in the world after clean water and so the scale of the problem is huge. Second, CO2 is an inevitable by-product of the chemical reaction in cement production. There are a bunch of complex chemical reactions that take place, but for the purposes of understanding why CO2 is inevitable, the whole thing can be simplified to this: Limestone (calcium carbonate CaCO3) is heated using fossil fuels in a cement kiln at more than 1450°C to break down into calcium oxide (CaO) and CO2 [CaCO3+heat➔ CaO+CO2]. The CaO then goes on to form more complex minerals that ultimately form the raw granular form of cement called Clinker or Portland Clinker. Clinker is further ground and blended with other additives to make commercially available cement.

About 50~60% of the CO2 emissions from cement manufacture can be attributed to this chemical reaction. Another 30~40% of the emissions are attributable to the combustion of the fossil fuels in the kiln, and the last 5~10% is attributable to the use of electrical energy to power the plant and machinery.

Avoiding the chemistry related CO2 would need a complete reinvention of this century’s old construction material, starting from a completely new raw material. Alternate chemistries are being explored instead of limestone, for example magnesium hydroxide from seawater. From a safety standpoint, construction materials need to pass various regulatory checks, and these new materials are yet to get there. Another approach has been to capture a part (~10%) of the CO2 produced during cement manufacture and reinject it into the cement before it is used at the construction site, thereby implementing a variant of CCS.

To abate the fossil fuel component of CO2, a promising technology I have seen is the RotoDynamic Heater from Coolbrook. This is a novel method to superheat air electrically using turbomachinery principles, similar to how jet engines work. With traditional electric heaters, you could heat air up to about 500~600°C, whereas the thermal process of cement manufacturing requires temperatures greater than 1450°C. In the RDH solution, air is first accelerated to supersonic velocity using an electric driven turbo machine, creating intense kinetic energy. It is then slowed down very quickly in a diffuser, whereby the kinetic energy is converted to thermal energy (heat) through compression, turbulence and friction. This allows to superheat air to 1700°C that can then be fired into the kiln, thereby replacing fossil fuel power with electrical power.

Meanwhile, there are some measures that the cement industry already practices. 5~10% of the CO2 emissions come from the use of electricity. A significant portion (~40%) of this can be offset with the use of Waste Heat Recovery Systems (WHRS). The cement manufacturing process involves a lot of thermal energy, a lot of which goes waste. The WHRS systems use this thermal energy to produce steam and thereby, generate electrical power on-site. The rest of the electrical CO2 emissions could be offset using renewable energy sources. When RDH or similar technologies are commercialized to transition the heating process from fossil fuels to electricity, and the electrical sources are green, almost 40~50% of the CO2 emissions from cement could be mitigated.

Another low hanging fruit has been to just improve the overall cement manufacturing process efficiency and uptime. Software and automation have a big role to play there.

Traditionally, clinker (the “pure” cement) has also been mixed with up to 45% slag (a steel making byproduct) or 35% fly ash (a byproduct of coal combustion) to reduce the quantity of clinker needed per ton of cement. Another approach has been to use alternate fuels like discarded vehicular tires, discarded plastic, biomass (wood chips, rice husk and other agricultural waste), etc, instead of coal to fire the cement kiln. These alternate fuels should have lower carbon emissions compared to fossil fuels to make sense. As explained elsewhere, burning biomass is considered to be carbon neutral if the biomass is sustainably sourced. Another advantage of using alternate fuels is that they reduce the mass of waste going into landfills, thereby solving another civic problem. This transition to alternative fuels is in early stages and comes with its own set of challenges like sourcing these fuels, sorting and segregating them, treating flue gas pollutants, etc.

Steel Production

The most widespread steel making process is the integrated blast furnace (BF) and basic oxygen furnace (BOF) process. Iron oxide (FexOy) from iron ore is reduced to iron (Fe) inside the blast furnace with coke (C) as a reducing agent. The product of the blast furnace, carbon-rich pig iron, is then processed into steel in a basic oxygen furnace, where oxygen is blown through the molten pig iron to reduce its carbon content. 73% of the global steel production comes from this process.

Like cement, it is a complex chemical process, but one that produces CO2. A representative reaction starts with ferric oxide: [2 Fe2O3 + 3 C → 4 Fe + 3 CO2].

But the similarity with the cement chemical process ends there. Unlike cement, where the carbon is integral to the raw material (CaCO3), the BF process introduces carbon to remove the oxygen from the iron oxide. And this crucial difference makes all the difference.

An alternate, though not very popular steelmaking method is the direct-reduced iron (DRI) route. DRI or sponge iron is produced by directly reducing iron ore pellets without melting, usually using a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen derived from natural gas. This method provides the final steel product with around 36% less CO2 emissions. But that’s not why I bring it up. This is currently a mature manufacturing process, but popular only when natural gas is very cheap.

A consortium in Sweden has piggybacked on this DRI technology and is working to develop what is the most promising technology for commercial scale fossil free steel, the HYBRIT technology. Their pilot plant is already operational at a capacity of 1 ton/hr of steel. A commercial scale demonstration plant is under construction to produce 1.35 million tons per annum (~150x the pilot plant scale), slated to be operational in 2026. The HYBRIT technology uses hydrogen instead of carbon as the reducing agent. The simplified chemical reaction is: [Fe2O3 + 3 H2 → 2 Fe + 3 H2O].

Green hydrogen is used for this process. Now, instead of CO2, the byproduct is water vapour. And this water vapour again goes back to the electrolysers for generating more green hydrogen. The entire value chain is now with zero fossil fuel or CO2 imprint. Imagine a future where the steel production process globally moves from one that is producing massive amount of CO2 to one producing massive amounts of water. That’s the kind of breakthroughs that we need. But this transition is not going to be easy. An established blast furnace costs billions to set up, and it is going to take a lot of incentive to shut it down and recreate a completely new hydrogen-based production line. I’m hopeful that this technology matures fast and at least the newer plants can come up with this technology. I also wish companies in China and India already start to do their own pilots without necessarily awaiting the outcome from HYBRIT to speed up the scale and cost economics.

While we await mass adoption of HYBRIT, a low hanging and proven solution for low emission steel is to maximize the recycling of steel scrap. An electric arc furnace (EAF) is charged with steel scrap, which is melted to form new steel. Renewable energy can power EAFs, reducing carbon emissions from the scrap EAF process to almost zero. The main challenges are availability of sufficient volume of scrap and the availability of suitable quality. These issues can be mitigated with proper policy measures for end-of-life vehicles, ship breaking, etc. Major steel producers are already working towards expanding EAFs as part of their portfolio. The recent announcement by Tata Steel to build a 3.2 million ton per annum EAF capacity in Port Talbot, UK is a good example of this trend. Tata Steel expects this process to “cut on-site CO2 emissions by 90% compared to previous blast furnace-based steelmaking – equivalent to 1.5% of the UK’s total direct CO2 emissions”.

Sector 3: Agriculture and Land Use

Moving on to the next major sector, agriculture, it must come as a surprise to many as a perpetrator of GHG emissions. In fact, with 22% share of the global GHGs, it is not very far behind industry or electricity. The main difference is that agriculture’s Achilles’ heel is not CO2, but methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O), both of which have far greater 20-year global warming potential than CO2 at 84x and 298x respectively see detailed endnotes.

With global population expected to grow from today’s 8 billion to 10 billion by 2100, and more poor are lifted out of poverty, and the rest get richer, we are going to need a lot more than 25% more food, probably 70% more. This problem is slated to get worse.

Emissions from farm animals

So where do all these emissions come from? The methane is mainly from animal burp and fart. Humans rely on gut bacteria in our large intestine to break down various insoluble fibre like cellulose, grains, seeds and other dietary fibre that cannot be broken down by our digestive enzymes. Cows have an even bigger problem because their diet is almost entirely consisting of such difficult to breakdown grass and plants. So, they have 4 stomach chambers where the bacteria break down the cellulose, fermenting it (enteric fermentation) and producing methane as a result. This also happens with goat, sheep and other ruminants. And when these animals poop, the decomposing poop releases copious amounts of nitrous oxide and some amount of methane, sulphur and ammonia.

It turns out that the amount of methane that a cow emits depends on where the cow lives. Cattle in South America emit 5 times more GHG than the ones in North America, and the ones in Africa emit even more. This probably relates to the breed, their veterinary care, the feed quality and manure treatment. So, one mitigation action is to try and replicate the best practices and breeds from the least emitting locations to other cattle farming locations. This is easier said than done since cattle farming in the poorer location is not a mass industry, but a scattered and fragmented practice.

Going vegan is another good option. But unfortunately, eating meat is almost a cultural identity for many and this culture change is going to take time, but there is hope. The vegan wave is catching on and maybe a few more wildfires and some awareness will move the needle. For those willing to make small changes, the option of plant-based meat exists. This industry is maturing and growing. For those not convinced about plant-based meat, you will have the option of lab grown meat in the not-too-distant future. Lab grown meat starts with a few cells drawn from a living animal and cultivating them into forming only the tissues we are used to eating, not the whole animal. This way, animal cruelty is also avoided and there is no GHG emission. But right now, this is still experimental and expensive. But if the stupendous growth of lab-grown diamonds is anything to go by, there should be no reason to back off from lab-grown meat either.

By the way, here’s the lowdown on the calorific conversion efficiency of meat. A chicken needs to be fed 2 calories worth of grain to give 1 calorie of meat. A pig eats 3 times as many calories as we get from its meat, and a cow needs 6 calories for each calorie of meat. That doesn’t sound very efficient and is another good argument to go vegan. Unfortunately, the global meat consumption is rising faster than the population.

Reducing food waste is probably the lowest hanging fruit in cutting emissions. Globally, about 20% of food is simply thrown away, allowed to rot, or otherwise wasted. In the US, it is 40%. That’s unfair to the people who don’t have enough to eat, bad for the economy, and bad for the climate. Not only are the GHGs emitted while cultivating the food going waste, but the rotting food produces methane equivalent to 3.3 billion tons of CO2.

Emissions from fertilizers

Fertilizers used in farming is another major source of GHG. Plants need nitrogen for photosynthesis. In the wild, this is provided in the form of ammonia by various microorganisms in the soil using a process called nitrogen fixation. But natural nitrogen fixation isn’t sufficient for large scale agriculture, and so this is supplied through synthetic fertilizers. Every stage of the fertilizer cycle produces GHG. Fossil fuels are used in manufacture and transportation. After applying fertilizer to the soil, only about 50% of the nitrogen is used up by the plant, the rest escapes and forms nitrous oxide in the atmosphere. All told, about 1.5 billion tons of GHG is attributable to fertilizer.

Solutions to this include getting farmers to be a bit more judicious about fertilizer overuse. But in practice, they will rather err on the side of caution and overuse since the price of fertilizer is not much compared to a potential loss of yield. There’s work being done to develop new varieties of crop that can recruit bacteria to fix nitrogen for them, thereby reducing the need for fertilizer. Another angle is to develop microbe additives that can be added to soil instead of fertilizer to maximize natural nitrogen fixation. These technology solutions will need to work closely with policy makers and with grassroot farmer support organizations to be successful.

Deforestation

Last, but not the least, under this category is the problem of deforestation. The world has lost more than a half million square miles of forest cover since 1990 viz. an area bigger than South Africa or Peru. The Amazon rainforests are being cleared for pastureland for cattle to feed the beef demand in the US. In Africa, forests are being cleared to grow food and fuel. In Indonesia, they are cleared to grow palm trees. Deforestation has multiple GHG impacts. First, that much less CO2 is now going to be absorbed from the atmosphere, thereby leading to net additions in GHG. Second, forests are sometimes cleared by burning them down, and this releases addition CO2 into the atmosphere, carbon that was otherwise locked into the tree. Third, CO2 and other GHGs that are trapped in the soil gets disturbed and released into the atmosphere. Overall, about 3 billion tons of GHG additions is attributable to deforestation.

And then, of course, is the heart wrenching impact of deforestation on wildlife. An orangutan baby takes about 10~12 years to learn her way around her forest to the best places for her fruit. But with the forest practically being chopped from under their feet, they are now a critically endangered species. This is the story of many forest dwellers today.

These are complex problems that need more than a technological solution. Forests may grow in one country but are a global GHG sink. We need political and economic solutions, including paying countries to maintain their forests, enforcing rules designed to protect certain areas, and making sure rural communities have different economic opportunities.

Here’s a reality check on the infamous tree plantation gigs in the corporate world. I just did a quick calculation of the CO2 emission attributable to a business class roundtrip flight, with a stopover, from Europe to India. As per this site, that would be more than 10 tons. On the other hand, the average tree absorbs about 4 tons of CO2 over the course of 40 years. So, the next time an international delegation visits, remember that the photo opportunity of them planting a tree on your campus is sending the wrong message to your organization. That plant isn’t going to make a dent to GHG emissions attributable to their trip. Your organization needs to do a lot more meaningful stuff. Using that opportunity to abstain from planting that tree but instead, spreading awareness about climate change may do more good.

Don’t get me wrong. I am all for tree plantation. But the objective must be clear. A tree on the office campus is only an aesthetic statement. A massive tree plantation drive, supported by an NGO that is working towards a larger objective and who can coordinate this on a larger scale can help in multiple ways. The climate change objective is one. There are other significant objectives like rewilding and providing an ecosystem for wildlife, birds, insects, bees, etc. It could be an environmental objective like protecting soil degradation or creating a natural barrier to the elements. But for those of us who think that odd campus tree plantation absolves us of our GHG emission sins, please remember, that was just a placebo.

Sector 4: Transportation

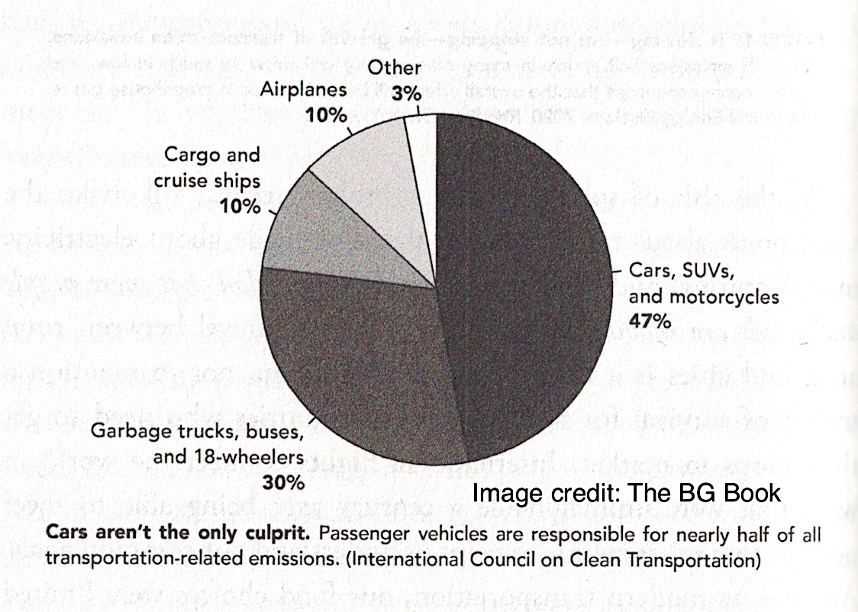

Because of how much it is in the news, most people would think transportation is the biggest cause of GHG emissions. Actually, it is only 16% of global GHG emissions. However, in the US, where people drive and fly a lot more, transportation is the biggest of all emitters, even ahead of electricity. This sector includes aviation, trucking, marine shipping, railway, passenger vehicles and light commercial vehicles. The below pie chart gives a breakdown between these categories. As can be seen, passenger vehicles contribute to 50% of the emissions.

Passenger vehicles (PVs) and Light Commercial Vehicles (LCVs)

A battery electric vehicle (BEV) is no longer a novelty. With the rapid drop in battery prices, the lifecycle green premium on BEVs is now starting to be negative i.e. the overall cost of buying and owning a BEV is less than that of an ICE (Internal Combustion Engine) vehicle. This depends on how long one holds on to the vehicle, the typical distance driven annually, government incentives, how smartly priced was the BEV at the time of purchase, and the relative price of fuel versus that of electricity.

In an Indian scenario, we can be reasonably sure that fuel will stay expensive, and prices will rise, whereas with more capacity being added to the grid, electricity prices should not hurt as much. Many states are providing incentives in the form of lower road and registration taxes for BEVs. And the competition is hot enough for manufacturers to be pricing BEVs reasonably. If you can afford one, I am a strong proponent for a BEV purchase. Let not the noise of disinformation confuse your decision. Rising demand will further bring down prices and will help expand the charging network. The range anxiety is a reality, but with proper planning, people have been able to manage this quite well. It’s a simple question of how committed you are to doing your bit in preserving Mother Earth.

Apart from lifecycle costs, there is another strong reason I advocate a BEV, especially for Indian city driving. Most studies of BEV versus ICE cars have focused their attention on driving conditions on roads in developed countries. To put it mildly, Indian city traffic operates at a very different dynamic. If you are lucky to not be stuck in a traffic jam, you are invariably in start/stop traffic. Your foot is forever shuttling between the brake and accelerator. This leads to dramatically less fuel efficiency and more importantly, dramatically higher pollution. I haven’t seen a serious study that factors this aspect into the BEV versus ICE debate. For Indian cities, the PV and commercial vehicle segment is not just a big GHG problem, but also a massive polluter. While a BEV’s efficiency will also drop with start/stop traffic, that drop isn’t anywhere as bad as that of an ICE and in standstill traffic you don’t consume fuel for idling. But most important, idling and start/stop are when an ICE’s pollution emissions are at its worst, whereas a BEV keeps your city clean.

There is also the debate that most of Indian electricity is produced in coal fired power plants, and so a BEV is only moving the GHG emissions from one location to another. That is only partially true for three reasons. First, India is dead serious about decarbonizing its electricity production. So, let’s not make this a chicken and egg debate, this situation will change. It is also possible that you have your own solar panels at home and use that for your BEV charging. The second aspect comes back to fuel efficiency. A coal-based power plant produces power at a much higher fuel conversion efficiency than will ever be possible in an ICE. Per joule of energy produced, a coal plant will have much less GHG emissions than that of an ICE in the best of conditions. Add to that city driving, and we don’t have the best of conditions, right? So, even if my BEV is charged using coal-based power, I think that is better than an ICE car for climate change and pollution. Third way of looking at this debate is that major incremental additions are happening is renewable energy capacity. This incremental capacity is far more than the incremental demand from BEVs. So, we can consider that all BEVs are essentially fed from renewable energy sources.

Apart from BEV, there is also a lot of hype around hydrogen cars. We covered the fuel cell technology previously under the Green Hydrogen topic. A hydrogen car is also an EV, but instead of carrying a battery that stores energy for the ride, it stores the energy as hydrogen in a tank. That hydrogen is converted to electricity in the on-board fuel cells to power the EV. There are already some manufacturers with hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV) car models launched commercially on a small scale. The basic technology is proven, but the many practical challenges I spoke about under the Green Hydrogen topic are to be ironed out. For now, these are still very early days, and I wouldn’t bet on it for the PV segment in the short term. Nevertheless, there is rapid development in this field from the Japanese and if they succeed in commercializing this on a mass scale, that would be wonderful. In the long term, it could eventually become another option. When it does, that would be nice because over the complete lifecycle of the car, a FCEV would be a greener option than a BEV because you don’t have the problems associated with the manufacture and disposal of the batteries.

Next on the list for PVs is biofuels. Today, ethanol is already an additive to petrol in India and has reached a blending rate of about 15% with a target to reach 20%. Ethanol is produced from fermentation of sugarcane. And as with biomass, biofuels are also considered to be GHG neutral because the CO2 emitted during combustion is the same CO2 absorbed by the sugarcane during its growth. But this claim is highly suspect because of the additional emissions from fertilizers used in sugarcane farming and that from the ethanol production process.

Light commercial vehicles (LCVs) like an ecommerce delivery van or a city bus can be treated at par with PVs. They largely operate in a limited geography; they have access to charging infrastructure and operate reasonable daily distances while doing large annual distances. All factors that favour the economy of electric vehicles. So, the conclusions for PVs apply to them too, viz. transition to EV. In fact, for city buses, FCEV may be a viable option much before it becomes an option for cars because the refuelling infrastructure can be easier to set up. You need it only at the main bus depots.

Another interesting niche in the light vehicle segment that I came across recently is intra-city flying… air taxis, air ambulances, etc. A good example is The ePlane Co. These can certainly go electric as ePlane is already proving.